Table of Contents

We all know how we feel after a long day. Our muscles are tired, our legs heavy, our eyelids ready to close. Though sleep may seem as if it originates in the body, the brain controls each aspect of slumber, from the feeling of sleepiness to dreaming to waking up.

Every living organism, from the smallest to the largest, needs sleep. Sleep is an intricate process that involves light and dark signals, specialized genes, and an array of neurotransmitters and hormones. We do not simply “drop off” into sleep; our brains orchestrate this state of altered consciousness with complex precision.

Note: The content on Sleepopolis is meant to be informative in nature, but it shouldn’t take the place of medical advice and supervision from a trained professional. If you feel you may be suffering from any sleep disorder or medical condition, please see your healthcare provider immediately.

Where Sleep Begins: The Circadian Rhythm

The process of sleep starts with the circadian rhythm, a system of biological clocks located in the brain and throughout the body in organs and muscle tissue. Each clock consists of specialized pacemaker cells that operate on a 24-hour cycle.

The master clock, known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), contains approximately 20,000 nerve cells located in a section of the brain called the hypothalamus. The SCN functions as a built-in mechanism that keeps time and regulates sleep. (1) The genes within the pacemaker cells are designed to control sleep and waking using a combination of chemical signals, daylight and darkness cues, and other environmental indicators such as stress and meal times. (2)

Nerve cells

Nerve cells, or neurons, act as the nervous system’s unit of communication.

In addition to sleep, the circadian rhythm influences other key bodily processes, such as:

- Metabolism

- Heart rate

- Core body temperature

- Blood pressure

- Levels of certain hormones

Certain cells in the optic nerves are responsible for sending light and darkness signals to the brain. This helps signal the circadian rhythm to activate neurotransmitters that make us feel alert or sleepy. Each individual’s circadian rhythm is shaped by a combination of environmental cues, genetic predisposition, chemical release in the body, and lifestyle choices such as work and travel schedules.

The Role of Adenosine

Adenosine is found in every cell in the body, and has numerous important functions including expanding blood vessels and regulating heart rhythm. Adenosine is a byproduct of the degradation of a related molecule called ATP, which stores and transports energy within cells. (3)

Over the course of a day as ATP releases energy, levels of adenosine build up in the parts of the brain associated with feeling alert. This leads to the eventual “switching off” of neurotransmitters responsible for wakefulness and an increase in the drive to sleep.

The sleep-promoting hormone melatonin may also help increase levels of adenosine. These hormones and neurotransmitters work in concert with the circadian rhythm and light-dark signals to reduce alertness and bring on feelings of sleepiness. (4) Sleep rapidly diminishes levels of adenosine, leading to a gradual increase in alertness as morning approaches and light signals reach the brain.

FAQ

Q: Why does caffeine make us feel more awake? A: Caffeine fits into the body’s receptors for adenosine, blocking its sleep-promoting effects and increasing feelings of alertness.

Orexin: The Brain’s Sleep Switch

Orexin is a neuropeptide, a type of molecule that neurons use to communicate. Also known as hypocretin, orexin is produced by the hypothalamus, and helps to regulate appetite, arousal, and wakefulness. Arousal refers to the state of being awake and aware, with sensory organs able to perceive external stimulation. To determine whether an organism should be asleep or awake, the orexin system uses information from the metabolism and circadian rhythm, along with the influence of sleep debt.

Orexin promotes the state of wakefulness by activating brain chemicals with a significant influence on wakefulness, such as dopamine and histamine. The loss of orexin molecules appears to be at play in narcolepsy, which was recently determined to be an autoimmune disease. The body mistakes orexin molecules for an intruder and attacks them, a destructive process that typically begins in childhood or adolescence after a viral illness.

How Sleep Impacts the Brain

Even during the deepest stages of slow-wave sleep, the brain does not shut down or go dormant. Though sections of the brain rest at various times during sleep, the brain is active during all four sleep stages. Some of the brain’s nighttime activities include cleaning itself, processing emotion, and consolidating memories.

Housekeeping

During the third stage of sleep known as N3, white matter cells called glial cells expand and contract, allowing cerebrospinal fluid to enter channels in the brain. This fluid washes out toxic proteins and other metabolic waste, including substances associated with dementia such as amyloid and tau. (5)

Known as the “glue” of the nervous system, glial cells outnumber all other types of cells in the brain. Sufficient sleep may help reduce the risk of neurodegenerative diseases by giving glial cells adequate time to remove the debris that collects during waking hours. Chronic lack of sleep might allow this debris to accumulate and stick together, increasing the risk of incurable brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s. (6)

Recent research shows this type of cerebral housekeeping can continue in the absence of adequate sleep, but is more likely to malfunction. In studies of sleep-deprived mice, the brain’s cleansing process did not stop, but swept away parts of living nerve tissue instead of toxins and other damaging debris. (7)

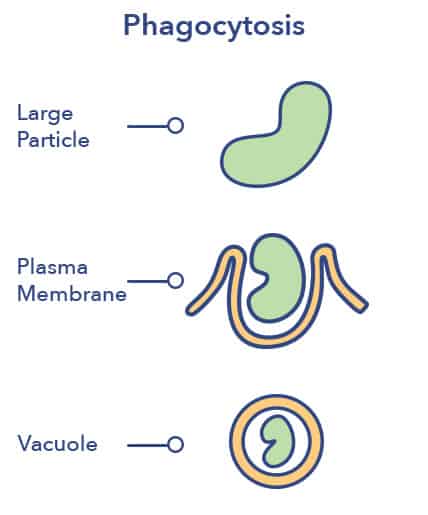

The process of debris removal in the brain and body is known as phagocytosis. During phagocytosis, a cell uses its plasma membrane to surround a particle and wall it off in a tiny pocket called a vacuole. Phagocytosis is healthy when cells consume and destroy harmful substances such as bacteria, but when phagocytosis misfires due to sleep loss and consumes essential nerve cells, it may be described as the brain eating itself.

Though the studies of mouse brains have not been replicated in human beings, sleep deprivation in the human population is known to cause excessive build-up of the same toxic proteins associated with dementia.

Phagocytosis

The engulfing of a pathogen or particle of cell debris by another cell. Phagocytosis is one of the essential functions of the immune system.

Emotion Processing

Recent research demonstrates that sleep helps the brain process, regulate, and remember emotions and emotional experiences. Sleep loss impairs performance on memory tests and increases activation of the amygdala, the area of the brain associated with primitive emotions such as fear and other defense responses. (8)

Other studies show that the brain reacts more negatively to all stimuli when sleep-deprived, increasing feelings of sadness, depression, and irritability. Sleep appears to have a significant impact on emotional reactivity as well as the ability to control emotional responses. Sleep loss can cause repetitive negative thinking, as well, making it more difficult for those who are sleep deprived to shift to a positive frame of mind. (9)

MRI imaging of volunteers shows that adequate sleep helps diminish emotional responses and memories associated with disturbing images. Study subjects who slept between viewing sessions displayed less emotional stress on imaging, while those who did not sleep showed higher levels of activity in stress-sensitive areas of the brain. (10)

Sleep may help in the processing of emotion due to the absence of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine in the brain during REM sleep. During REM, vivid dreaming occurs and norepinephrine is at its lowest point in the 24-hour sleep-wake cycle. Norepinephrine is associated with stress and emotional reactivity, and at high levels may be indicative of a mood disorder such as depression or post-traumatic stress disorder.

FAQ

Q: What is norepinephrine? A: Norepinephrine is a neurotransmitter that incrreases alertness, prepares the brain and body for action, and focuses attention. It also increases feelings of restlessness and anxiety.

Memory Consolidation

Sleep appears to be instrumental in learning and memory consolidation as well as emotional processing. (11) During waking hours, the firing of multiple neurons at once leads the brain to pay attention to certain people, events, or stimuli. A car that passes by won’t excite neurons, while running into an old friend will. These notable waking experiences join the queue for memory consolidation during sleep.

During sleep, in an environment without competing stimuli or waking consciousness, the brain selects certain experiences and stabilizes them, locking them into memory. (12)

Studies show that brain activity during REM sleep increases significantly after novel experiences or those that require memorization or the understanding of complex concepts. (13) The role of REM sleep in memory processing and consolidation was controversial for decades. It was once theorized that REM sleep’s only role in memory consolidation was to provide an unconscious environment that prevented nighttime experiences from overwriting those that occurred during wakefulness. (14)

Sleep scientists now know that neurochemical conditions in the brain during sleep are important for the processing of memories. Part of sleep’s function as a whole seems to be the consolidation of memories, as well as the selection of important aspects of experiences to store for later recall.

Last Word From Sleepopolis

The brain is the engine of sleep. From the master clock of the circadian rhythm to the timed release of neurotransmitters, sleep is a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors.

Sleep is essential to all living beings, from fruit flies to whales. Though sleep is individual, the process is universal. Sleep protects and regenerates the body, and allows us to process the emotions and memories that make us human.

References

- Welsh DK, Takahashi JS, Kay SA., Suprachiasmatic Nucleus: Cell Autonomy and Network Properties, Annual Review of Physiology, 2010

- Ethan Buhr, Russell N Van Gelder, The Making of the Master Clock, Insight, Aug. 20, 2014

- K.A. Jacobson, Adenosine, Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, 2009

- Vacas MI, Sarmiento MI, Pereyra EN, Cardinali DP., Effect of adenosine on melatonin and norepinephrine release in rat pineal explants, Acta physiologica et pharmacologica latinoamericana : organo de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Ciencias Fisiológicas y de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Farmacología, 1989

- Frank MG., The Role of Glia in Sleep Regulation and Function, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Jan. 28. 2018

- Dzamba D, Harantova L, Butenko O, Anderova M., Glial Cells – The Key Elements of Alzheimer´s Disease, Current Alzheimer Research, 2016

- Michele Bellesi, Sleep Loss Promotes Astrocytic Phagocytosis and Microglial Activation in Mouse Cerebral Cortex, The Journal of Neuroscience, My 24, 2017

- Tempesta D, Socci V, De Gennaro L, Ferrara M., Sleep and emotional processing, Sleep Medicine Reviews, Dec. 22, 2017

- Jacob A Nota, Sleep Disruption is Related to Difficulty Disengaging Attention from Negative Emotional Images in Individuals with Elevated Transdiagnostic Repetitive Negative Thinking, Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, Mar. 2018

- Walker MP, van der Helm E., Overnight Therapy? The Role of Sleep in Emotional Brain Processing, Psychological Bulletin, Sep. 2009

- Philippe Peigneux, Are Spatial Memories Strengthened in the Human Hippocampus during Slow Wave Sleep? Neuron, Oct. 28, 2004

- Boyce R, Williams S, Adamantidis A., REM sleep and memory, Current Opinion in Neurobiology, June, 2017

- Adrien Peyrache, Replay of rule-learning related neural patterns in the prefrontal cortex during sleep, Nature Neuroscience, 2009

- Rasch B, Born J., About Sleep’s Role in Memory, Physiological Reviews, Apr. 2013

Subscribe Today!

Get the latest deals, discounts, reviews, and giveaways!