Table of Contents

For some people, falling asleep and waking up goes just as expected: They drift off and make their way through the four stages of sleep without incident. For others, waking up during the REM sleep stage is a nightmarish experience. In a condition known as sleep paralysis, those who experience it are awake and aware, but they’ve temporarily lost the ability to move.

And while sleep paralysis only affects a small portion of the world’s population, it’s ubiquitous.

In China, sleep paralysis is known as “ghost oppression.” In Egypt, it is described as an attack by the jinn; in Newfoundland, it’s known as the “old hag phenomenon,” and in the United States, sleep paralysis has been interpreted as an alien abduction.

Sleep paralysis may not be dangerous, but understandably, it can be pretty frightening.

What Is Sleep Paralysis?

According to Dr. Daniel Rifkin, founder of Ognomy, “during REM sleep, our brain shuts off all of our muscles so we can’t act out our dreams. [That temporary paralysis] kind of protects us from diving off our bed or tackling the dresser next to our bed.” He explains that in sleep paralysis, the brain wakes up but the body is still turned off, leaving us unable to move. “This ultimately results in a very scary situation where you are awake, but you can’t move, and you feel paralyzed,” Rifkin says.

While sleep paralysis is a normal part of REM sleep, it’s considered to be a disorder when that paralysis occurs outside of REM sleep. Sleep paralysis typically occurs at the onset of sleep (hypnagogic hallucinations) or when waking (hypnopompic hallucinations), and episodes can last anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes. Understandably, the longer an episode goes on, the more likely it is to trigger a panic response.

Types Of Sleep Paralysis

There are two types of sleep paralysis.

Isolated sleep paralysis is sleep paralysis that occurs outside of sleep disorders like narcolepsy. It is estimated that as much as 40 percent of the general population will experience isolated sleep paralysis at least once in their lifetime.

Recurrent Isolated Sleep Paralysis (RISP) is a parasomnia marked by multiple episodes (at least two in six months) of isolated sleep paralysis. RISP is often associated with considerable distress, anxiety, or fear around sleep.

Who Is Most Likely To Have Sleep Paralysis?

Sleep paralysis affects approximately 7.6 percent of the general population. Some people may experience sleep paralysis once in their lifetime, though others may have recurrent episodes of sleep paralysis. Prevalence and Clinical Picture of Sleep Paralysis in a Polish Student Sample

While sleep paralysis can begin at any age, initial symptoms and episodes tend to make an appearance in childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood for many. Research shows it affects women slightly more than men, it’s more common when sleeping in a supine position, and there is some evidence to support a higher prevalence of sleep paralysis among non-White populations.

Sleep Paralysis Causes And Symptoms

While researchers have yet to pinpoint the exact cause of sleep paralysis, they have identified risk factors associated with the parasomnia.

According to Rifkin, “anyone can experience sleep paralysis if they’re super sleep deprived. It can also occur alongside sleep disorders that make you sleep deprived, like sleep apnea and narcolepsy.”

In addition to sleep disorders, psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders, social phobias, panic disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) all seem to be contributing factors to sleep paralysis. Moreover, those who experience sleep paralysis often report stressful events, emotional triggers, and significant work or life events leading up to the episode.

Other factors that may contribute to sleep paralysis are

- Alcohol consumption

- Exposure to traumatic events

- A family history of sleep paralysis

Symptoms Of Sleep Paralysis

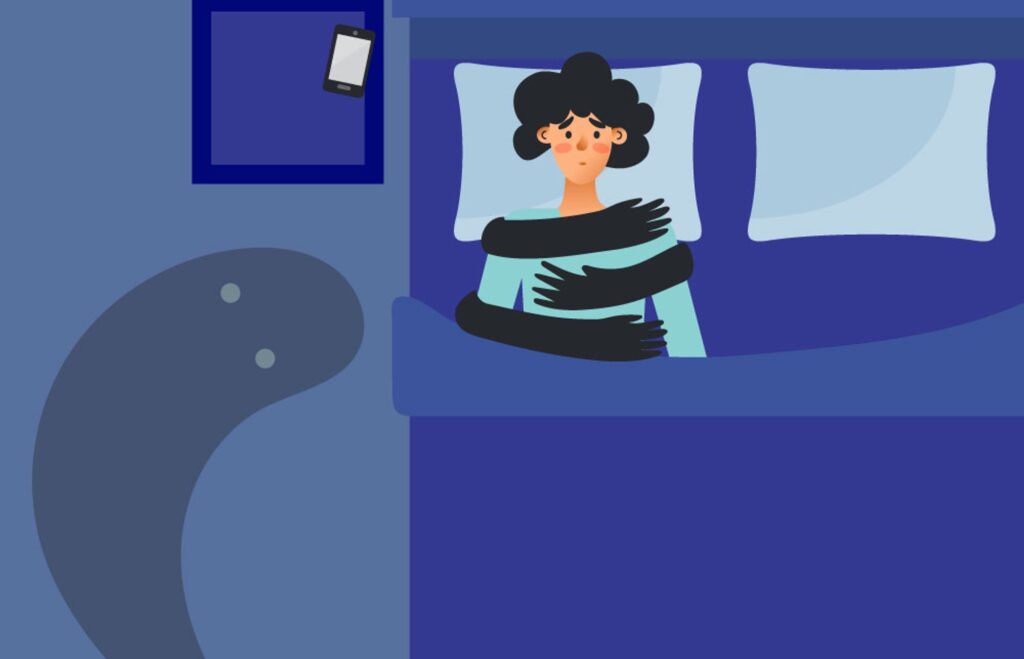

While waking up without the ability to move is a hallmark of sleep paralysis, that’s certainly not the end of it. Sleep paralysis episodes are also often accompanied by a range of physical symptoms and terrifying (and sometimes bizarre) hallucinations.

Physical symptoms of sleep paralysis include:

- Paralysis in your limbs

- Heart palpitations

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

- Nausea

- Inability to speak

- Sense of suffocation

- A choking feeling

Fear, panic, and helplessness are hallmarks of sleep paralysis, and interestingly, research shows that extreme fear reactions during sleep paralysis never go away for most people. The fear associated with sleep paralysis is so deep-seated that even when someone has had multiple episodes of sleep paralysis or an understanding of its mechanisms, they’re still terrified whenever it happens.

Hallucinations Associated With Sleep Paralysis

The physical symptoms of sleep paralysis are often accompanied by very intense, vivid, and frightening hallucinations.

There are three types of hallucinations associated with sleep paralysis.

Intruder hallucinations are marked by the perception of a dangerous intruder or an evil presence in the room.

Incubus hallucinations often cause the person to feel like they’re being choked or suffocated and tend to occur alongside intruder hallucinations.

Vestibular-motor hallucinations cause the person to feel like they are moving, flying, or having an out-of-body experience.

Is Sleep Paralysis Dangerous?

Although sleep paralysis may feel terrifying in the moment, it’s not dangerous, and there are no known long-term health consequences.

“If you are experiencing sleep paralysis once in a while, it’s not something to worry about, but there is something that might be going on with your sleep. If it’s occurring frequently, it could be associated with another sleep disorder, like narcolepsy,” says Rifkin. In that case, you may want to speak with your doctor to rule out the possibility of a more serious sleep disorder or health condition.

It’s also worth noting that anxiety disorders do play a role in sleep paralysis, and the two can be cyclical. While anxiety can exacerbate sleep paralysis, the heightened fear levels commonly associated with sleep paralysis may exacerbate anxiety. The net effect of this relationship may ultimately be short sleep and poor sleep quality, which can lead to even bigger issues. Taking the proper steps to manage anxiety is likely the best recourse for anxious sleep paralysis sufferers.

What To Do If You Wake Up With Sleep Paralysis

This may not be what anyone wants to hear, but there are no direct strategies to treat sleep paralysis during an active episode or to get someone out of it faster.

Anyone who regularly experiences sleep paralysis is probably best served to talk with their doctor to manage the physical and psychological factors that play a role in triggering the episodes.

Treatments For Sleep Paralysis

Like most parasomnias, treatments are focused on addressing underlying health conditions and sleep disorders, as well as making lifestyle changes and improvements to your sleep hygiene, such as:

- Maintaining a consistent sleep and wake schedule

- Adjustment your sleeping environment to eliminate noise and light

- Avoid sleeping on your back

- Establish a soothing bedtime routine

- Eliminate caffeine and alcohol, especially in the evening.

- Turn off phones and other electronic devices at least a half-hour before bed.

- Get regular exercise

The Last Word From Sleepopolis

Sleep paralysis is a normal part of REM sleep, but some people have woken up during REM sleep only to be aware and awake without the ability to move. Sleep paralysis is considered a benign parasomnia with no adverse health effects over the long term. There are no treatments to get someone out of sleep paralysis during an active episode, but treatment for the condition includes managing sleep disorders that could lead to sleep paralysis and maintaining good sleep hygiene.

Subscribe Today!

Get the latest deals, discounts, reviews, and giveaways!